What a wonderful way I had to begin the 63rd anniversary of the crash of Flying Tiger 923! Fellow survivor Paul Stewart, of Plano, Texas, rang my phone at noon on the anniversary date, Tuesday, September 23, 2025. It certainly set me back with joy!

Paul was one of the 20 or so brother combat paratroopers on board, all headed for Frankfurt, Germany. He is the single survivor I have spoken to in recent years. Probably the youngest of the active duty soldiers on the Flying Tiger at the time of the disaster, Paul says his family is all doing well, are grown and living nearby. He and his wife have moved into a comfortable senior living center where they can maintain an active retired lifestyle and be close to family.

Paul spent most of his working career as a lineman for the local electric system. A young 17 year old on 9/23/62, he is now 81. I was 21 at the time I am now 84. We are both happy to be here to celebrate another memorial year. We remember with love and high regards all of those on that fatal flight and those involved in so many ways.

The crash of Flying Tiger 923 in that stormy, frigid North Atlantic is far from forgotten by the remaining 48 survivors and their families and friends as well as:

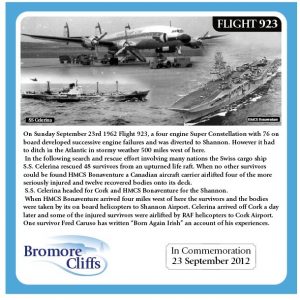

. . . the dozens of crew members and hundreds of their colleagues of the rescue ship, Swiss registered MS Celerina, a freighter loaded with wheat headed from Canada to Antwerp, Belgium, who provided food, clothing and shelter for the three storm-tossed days at sea to the survivors, all pulled from the lone, overturned life raft;

. . . and the crew and all of their support personnel of the US Airforce plane that intercepted the SOS calls from the failing Tiger and diverted its course from Scotland to New York to find, track and identify its location from above for the benefit of the rescue ship;

. . . and the hundreds, if not thousands of Canadian sailors of the aircraft carrier Bonaventure and four escort destroyers that were diverted to meet the rescue scene to provide medical and material assistance wherever possible;

. . . and the many hundreds of emergency rescue workers mobilized in the Republic of Ireland at the Cork and Shannon Airports, and the light keepers of the Galley Head lighthouse that served as point of coordination for rescue helicopters that took the most seriously injured from the Celerina to the Cork City airport and Mercy Hospital. By then, the Celerina was only some eight miles from the Irish coast and could not get any closer due to the unreliable outcropping of rocks in the shallower waters;

. . . and the lists of those involved goes on and on.

Unfortunately, there was no memorial update last year. As the author and editor of this Memorial Site, I must confess that I have not lost interest in the project . I have done very little to update these pages in recent years and none whatever in the past year. My latent case of PTSD rose up and slowed me down with deep feelings of sadness, which has made it difficult to write or talk about it. I am happy I was able to put so much into this memorial as I have, nearly 140 articles in total. I plan to make some significant updates, no matter how few readers may share memories of this event.

This is truly a memorial site for an event that was minimally publicized in the autumn of 1962. This was likely due to the heightening tensions over the threatening “Cuban Missile Crisis.” Do you remember that one? The Russians were sending missiles, some of which were believed to be carrying war-heads, some nuclear war-heads, to the island nation of Cuba. They were planned to be aimed at its closest neighbor, the USA.

I was unaware of this event until long later because I was preoccupied with being a combat parachute trooper dedicated to learning how to defend his nation and went for months as many others did with not paying attention to the news. The bottom line for us involved in the crash, is that most of the news was suppressed. Active combat troopers were not to be transported on the military transport system, even though there were only about 20 aboard, because it might reveal that strike force troops had been reduced during the quieter years following the Berlin Wall Crisis. The result was there was never a memorial created at the time for this event.

The demise of Flying Tiger 923 was a tragedy of tremendous proportions, especially to those directly involved, but not nearly so much as the tragedies of the Vietnam War that followed.

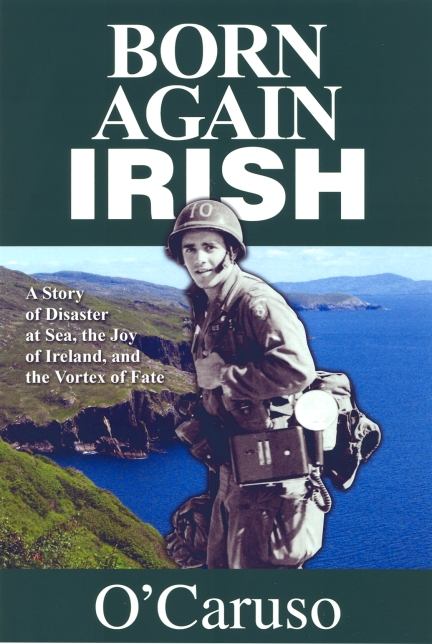

We are honored that you should be reading this and any of the 114 stories linked to the drop-down menu immediately below the picture of our very own tiger above. God bless everyone during this historic 63rd Anniversary Year. Thank you.

And following is a contribution by our friend, Garry Ahern, of Dublin, Ireland, who was there as a member of the first Emergency Fire and Rescue Team of the then-recently opened Cork Airport. He first penned this poem as part of an adult education night school program:

Ode to Big Bird (Flying Tiger 923)

A Memorial Poem for the “Big Bird” Flying Tiger Flight 923

by Garret Ahern, Dublin, Ireland

“Big Bird”

Out from New jersey,

Big Bird spreading wings,

Trundling east-ward, in

War-cold nineteen-sixty-two.

Three-score and ten-

And more aboard,

Service by the

Rhine in mind.

Far beneath lies rolling

Equinoctial ocean,

Unfriendly to the stricken

Super-Constellation.

Big Bird descending,

Inevitable ditching,

Frantic prayers implore –

Then impact, devastation.

Plucked from the inverted,

Overcrowded, life-raft,

The lucky greet new

Friends and shipmates.

In time, diverted,

The good ship “Celerina”

Nears its rendezvous.

Green fields plain to see.

By Galley Head, the

Helicopter’s chatter

Stampedes a flock of sheep.

Away west, wave-battered

Big Bird settles,

Low in the briny deep.

© 2012, Garry Ahern